JME in Action: My Top 3 for 44.4

The end of one year and the beginning of the next inevitably brings about ranked lists or photo collages on social media, news outlets, and television shows. While they can range from thoughtful to attention-seeking, this easy format offers us an annual opportunity to reflect and distill. This blog aims to capture the Top 3 things that the thematic articles illustrated for me in the latest Journal of Museum Education issue 44.4, The Past in the Present: The Relevancy of the History of Museum Education Today, and my thoughts about the future of this field.

#1 The best museums are rooted in their communities

The idea that the most relevant and responsive museums are those informed by and staffed by the communities they serve is a fundamental truth that is not recent. It was illuminating to read Jessie Swigger’s article, “Museums for Somebody: Children’s Museum Professionals and the American Association of Museums (1907–1922),” summarize the AAM presentations given by curators of the first three children’s museums in the US. She describes Delia I. Griffin, the first curator of the Boston Children’s Museum, and her vision for “Americanization” in the immediate post-World War I era: “Griffin’s version called on staff to reach out to immigrant communities, to invite them to serve as the authorities and educators about their own cultures and traditions, and to create exhibits and programs that began with the community rather than the museum” (p. 348).

In the century since Griffin’s presentation, children’s museums offer some of the best examples of community-based practice. However, the broader field still struggles to live this fundamental truth–why? Institutions rooted in the master narrative of colonial history, including the Western art history canon, continue to uphold White male patriarchy in their structure, personnel, and outputs. One could argue that children’s museums, at their core, embody the antithesis of this system. They are museums “for somebody rather than about something,” as Boston Children’s Museum Director Michael Spock asserted (p. 346), which values the primacy of children over objects. Further, both the feminization of child-rearing as “women’s work” and the focus on play, rather than words, as the main form of interpretation work to position children’s museums as counter to this system. I wonder if it will take another century before community-based practice, grounded in intersectional feminism and anti-racism, is the norm rather than the exception in the field–I hope not!

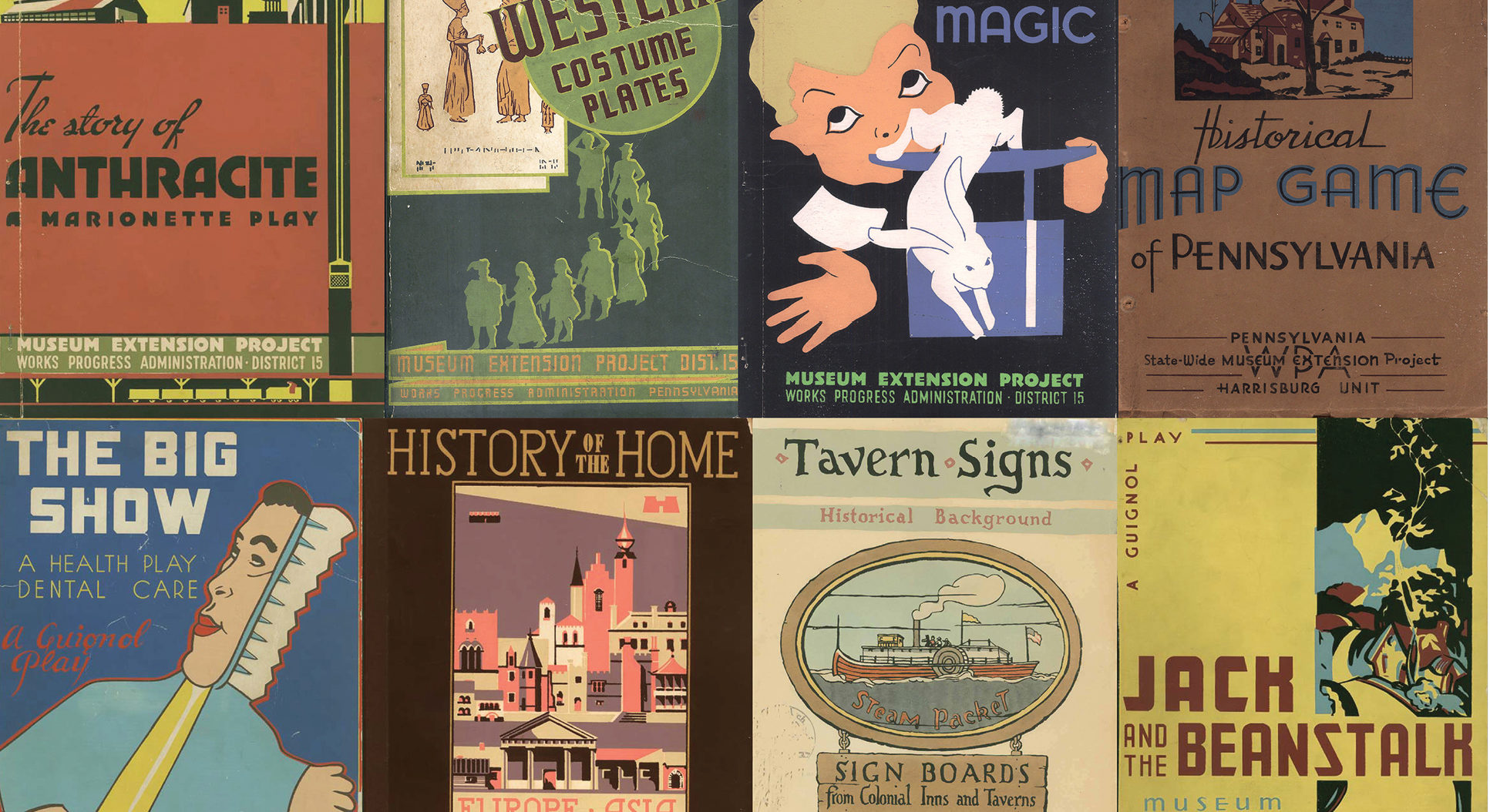

Another article that illustrates a historical example of museums becoming community assets is “The Influence of Progressivism and the Works Progress Administration on Museum Education” by Carissa DiCindio and Callan Steinmann. It was intriguing to read that the impetus for and implementation of this federally-funded program included “the idea that works of art would no longer be available solely for the wealthy and concentrated in urban areas, but something for everyone, no matter their race, location, or socioeconomic background, was a crucial piece of the WPA-FAP” (p. 356). How is this crucial piece actualized in museums today? In many ways, the modes are still the same or similar–travelling exhibitions and programs, community outreach, studio programs, and artist residencies. How can we as museum educators push ourselves and our field to move beyond broader access and greater diversity as the ends to community-based practice? How can we reframe this work as supporting the actualization of the equity and justice that our communities seek?

#2 The medium is the message

Three articles examined the history of three very different forms of interpretation: “From Watchful Grasshoppers to Rat Basketball: Pedagogical Lessons from the History of Live Animal Displays in Science Museums” by Karen A. Rader; “‘The Twenty-Four-Inch Box in Your Living Room is Not a Museum’ – Early Experiments in Museums Television” by Briley Rasmussen; and “Gallery Games and Mash-ups: The Lessons of History for Activity-based Teaching” by Elliott Kai-Kee. I am reminded of Marshall McLuhan’s famous phrase, “The medium is the message,” which means the characteristics of the medium itself are more impactful than the content communicated through that medium.

These articles thoughtfully examined these mediums of interpretation and inspired more questions! For example, live animal displays in science museums can range from an almost faithful recreation of the animal’s native habitat for visitors to observe, to inserting an animal into a highly controlled environment in order to demonstrate a particular behavior or phenomenon. What degree of human manipulation of live animal displays moves the actual learning experienced by visitors closer to or further away from the learning intended by exhibit designers? And how does the interpretation strategy used to support visitor engagement with the display impact the messaging and what’s learned? When the medium of television was an emerging technology back in the early 1950s, it offered museums an entirely new mode for outreach that did not exist before. How will museum television content need to innovate as the technology itself continues to evolve today? The incorporation of activities into gallery experiences is par for the course nowadays. Has gallery-based teaching evolved to the degree we imagine over time or is it a cycle with particular approaches, methodologies, and understandings that we continue to revisit over time? Fundamentally, how does our choice of medium reflect our foundational belief of how museum content is to be experienced?

#3 Walking the walk: Anti-racism as the modus operandi of museums

It was inspiring to read about the institution-wide and institution-deep commitment to anti-racism pedagogy in the article, “‘At Variance with Accepted Practice:’ Antiracist Pedagogies Within the Jewish History Museum” written by Bryan L. Davis and Ariel Goldberg. In all the talk about diversity, equity, and inclusion in the museum field, very few institutions have actually “walked the walk”, so to speak, of doing this work internally.

After observing the experiences of students in their museum, and with an understanding of the inequities the majority Latinx, Indigenous, and Black students are living in a border state, the Jewish History Museum recognized that the often assumed social good enacted by museums is just that, an assumption. In actuality, the harm of not recognizing and validating the truth of Latinx, Indigenous, and Black lived experiences in American society was enacted. They addressed this by looking inward and engaging in critical self-reflection and dialogue both as individuals and as an institution from the top down. They backed up their commitment in concrete ways by allocating staff time and resources, “Nearly a quarter of our staff labor is focused on educating ourselves through shared readings and holding internal discussions about inclusivity and antiracist practices” (p. 402-403). I think, most importantly, they challenged their own Whiteness and White privilege as part of their continual process to becoming anti-racist pedagogues. In a predominantly White field, the mental, emotional, and spiritual labour of diversity, equity, and inclusion work is often shouldered by Indigenous, Black, and racialized museum workers. How can White museum workers hold themselves and each other directly accountable in order to “walk the walk” of anti-racism?

Wendy Ng (she/her/hers) is an informal education specialist and advocate for equity and inclusion. She has managed educational programming in large public institutions including the Ontario Science Centre, Royal Ontario Museum, and Art Gallery of Ontario. She is currently on the Board of Directors of the Museum Education Roundtable and a member of the Editorial Team.