Convening Takeaways: Association of Art Museum Interpretation

Sometimes I wish I were a fantastic note taker. To my regret, my notes are scrappy from the Association of Art Museum Interpretation (AAMI) convening on June 6 and 7 in Chicago. My notes neither describe the exact words said, nor make clear attributions of who said what. But the spirit of the ideas from the last panel of the convening have been rumbling in my head since the meeting. The last session I attended was the Mini-Horizon Report panel discussion with Kristin Bayans, Gamynne Guillotte, Troy Smythe, and Michael Christiano; and moderated by Adrienne Lalli Hills. A sampling of my notes read as:

- Do not front load our projects, you can’t set [strict?] expectations when working with communities

- The process needs to be flexible and open, which can be slow and painful. We need emotional resilience.

- We are disrupting the process, so we need to consider how we are going to manage the ambiguity.

- This is particularly difficult with museum educators who want to have clear outcomes.

The phrase, museum educators who want to have clear outcomes, keeps playing over-and-over in my thoughts. As the panel participants stated, museums have challenges ahead in learning how to more effectively manage situations where things are often vague, need a deep trust to process, and belief that something useful and meaningful will emerge in spite of the uncertainty. But there was another edge to these panelists’ thoughts: when museum educators are so focused on setting goals, do we inadvertently limit the emergent possibilities of these projects and guide them too closely toward preconceived ends?

I’ve been teaching museum education and interpretation for many years and have worked on projects in many museums throughout my career. It’s been an ongoing effort of mine to get students, and even established practitioners, to figure out how to envision what they want to accomplish, and in turn, write effective goals. Setting outcomes helps set a direction, and, with the rise of evaluation practices, gives us a way to measure our success. Outcomes set the bar. Yet, how tight do these outcomes need to be? Would it be better to realize that outcomes do not need to be set in stone; and instead, add an outcome revision process for any project? Might a revision process help us manage the ambiguity necessary to be open – to act like we are willing to co-create experiences that will allow others to sway the possible direction our work takes?

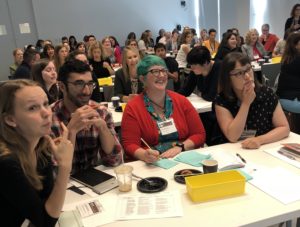

I don’t have answers yet, just questions. But it is this kind of deep provocation that tells me that going to this convening was a good idea. The June meeting was not the first meeting for this association, but it was the first that was held for two days, in a time and place different from the American Alliance of Museums Annual Meeting, where past convenings have been held since 2013. AAMI is just now formalizing its organization, and the convening offers a setting for those involved in art museum interpretation to exchange ideas face-to-face. Nearly 70 attendees listened to panelists, heard case studies, openly discussed the field’s professionalization needs, met in bird-of-a-feather conversations; and I believe, became inspired. That the participants are all connected with art interpretation meant that any two who attended had common ground, making conversation flow readily. One upside of two days with a small convening group is that you repeatedly see the same people, resulting in more than just one quick in-the-hallway conversation. Attendees can form deeper ties.

Throughout the convening, there were indicators that the field of art interpretation is working to become more defined, even though educators have been producing visitor materials and experiences for decades. There does not seem to be consistent language for the job titles of those doing the work of creating art interpretive materials, nor consistent language for the kinds of products produced. An activity with all participants brought this point home – and revealed a deep sense of humor we all carry about interpretation. The organizers showed pictures of classic interpretive items (labels, interactives, pamphlets), and asked table groups to both describe what these items are called in various institutions, and to reveal our more irreverent terms for them. Reported were descriptions like “text panel” as forced transition; “digital interactive” as petri-surface; “low-tech interactive” as the-things-that-go-missing; and one of my favorites, “resource area” as husband parking lot. While fun to laugh at our practices, the point is telling: it would be helpful to have a consistent vocabulary across institutions as there were multiple descriptors used for interpretive products.

On the second day, the convening took time to ask everyone to consider what hard and soft skills and consequent training are needed to do art interpretation. It is no surprise to me that the soft skills board had the most written comments on it. Some listed included: listening skills, collaboration skills, cultural competency, and respect. Soft skills seem to be the ones that people tend to worry about the most as to whether or not they can be taught. I sense that the field needs more discussions on what we mean by these skills, and we have to figure out how to insert these skills into job descriptions if they are so critical to the work. If we do add them, we will also need to be careful that we define them in some inclusive way as soft skills can be culturally determined.

I also attended a topical small group discussion centered on change management – a process highly dependent upon soft skills. My notes about this session include questions like: “How do we move the needle?” And, “how can we be at ease with this work that is so difficult?” Clearly there are skills and abilities needed to do the kind of visionary work among those who do it: interpretation is not just work that involves sitting alone in a room creating and writing – it is one of getting buy-in with others while honoring everyone involved.

The AAMI participants inherently seem to know that assisting meaning-making is no simple task – which takes me back to my notes on needing to live with ambiguity. AAMI is an emergent organization in the throes of defining who they are, and one seeking pathways for those who want to join the journey towards a stronger community of art interpreters. What shape it will take is still to be determined, as the organization is now forming its initial set of committees and providing a strong invitation to those who want to step up and shape the organization in its early phases. AAMI will hold their second convening next year in Detroit the last week of June. The convening will serve as their next point to assess their outcomes. For more information about AAMI, please see their new website.

Susan Spero teaches education and interpretation for the Museum Studies program at the John F. Kennedy University. Thanks to Adrienne Lalli Hills, AAMI steering committee member and program co-chair, who provided details about the AAMI convening and provided the images. Both Susan and Adrienne are members of the MER Board of Directors.